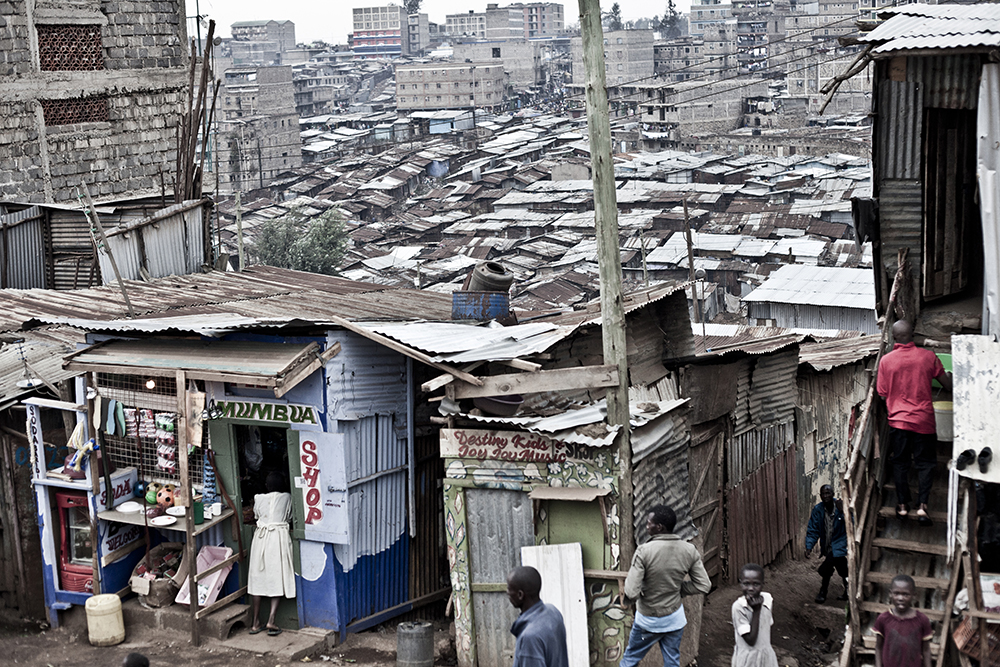

When the NGO Liveinslums called me in February 2012 to design and build equipment for a school using traditional, local materials and labour, I barely knew what a slum was. Members of the NGO, professionals from various artistic elds, offered me the chance to get in there and gave me the chance to read through their experiences. This helped me quickly realise that the Slum is a remarkably complex and detailed place where internal dynamics have created languages and a culture that is unique to that place, and that could only have developed under those conditions. I immediately turned my attention to the objects that are sold everywhere on the streets, and in the open markets. Simple things, for practical use, that are necessary to carry out normal daily activities: pots, mousetraps, shoes, shovels, ladles, buckets, lanterns... These objects belong, for all intents and purposes, to a domestic economy that has been created to meet the daily needs of hundreds of thousands of people living in the slums who do not have access to globalised consumer goods. The rubbish that surrounds them and invades the landscape is the raw material they use and by melting, cutting, riveting, weaving... They create reproducible objects in small series that feed a growing market, made up of people from the countryside who pour into the city. With exceptions being made for some customisations made by single ‘manufacturers’, these are invariant forms, grounded and always improvable, according to their functionality. The products from this slum possess a mysterious force that makes them difficult to place temporally: they are unquestionably contemporary, they have an urban character but, at the same time, they seem as old as the tribes that make up the Slum’s social fabric.

The many ethnic groups that live here bring their own objects, traditions, and rituals full of ancient meanings which inevitably converge and merge creating new languages for their new society. I think the strength of these products is to be found in their absolute necessity: they are what they seem; they are archetypes of this new culture. This is direct, simple expression, and as familiar as a moka would be for us. Their selection was dictated by how easy it was to get hold of them, due to them being consumer goods created for that specific place. A place where something is only designed if it is needed and produced with what can be found.

Exhibition “Made in Slums” 201 - Museo Design Triennale Milano

Photo Credits: Francesco Giusti, Filippo Romano